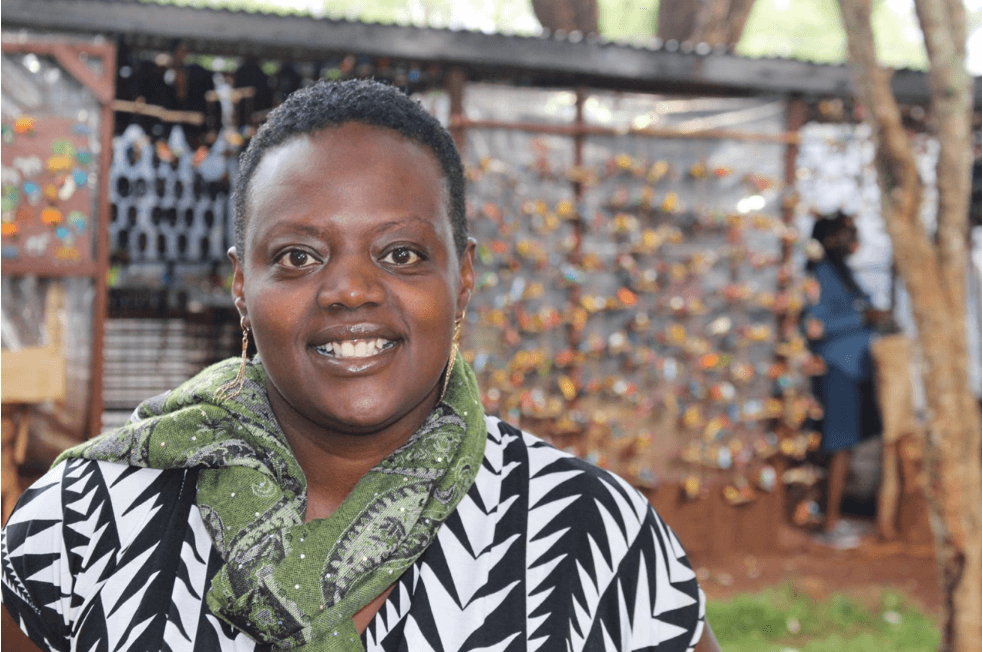

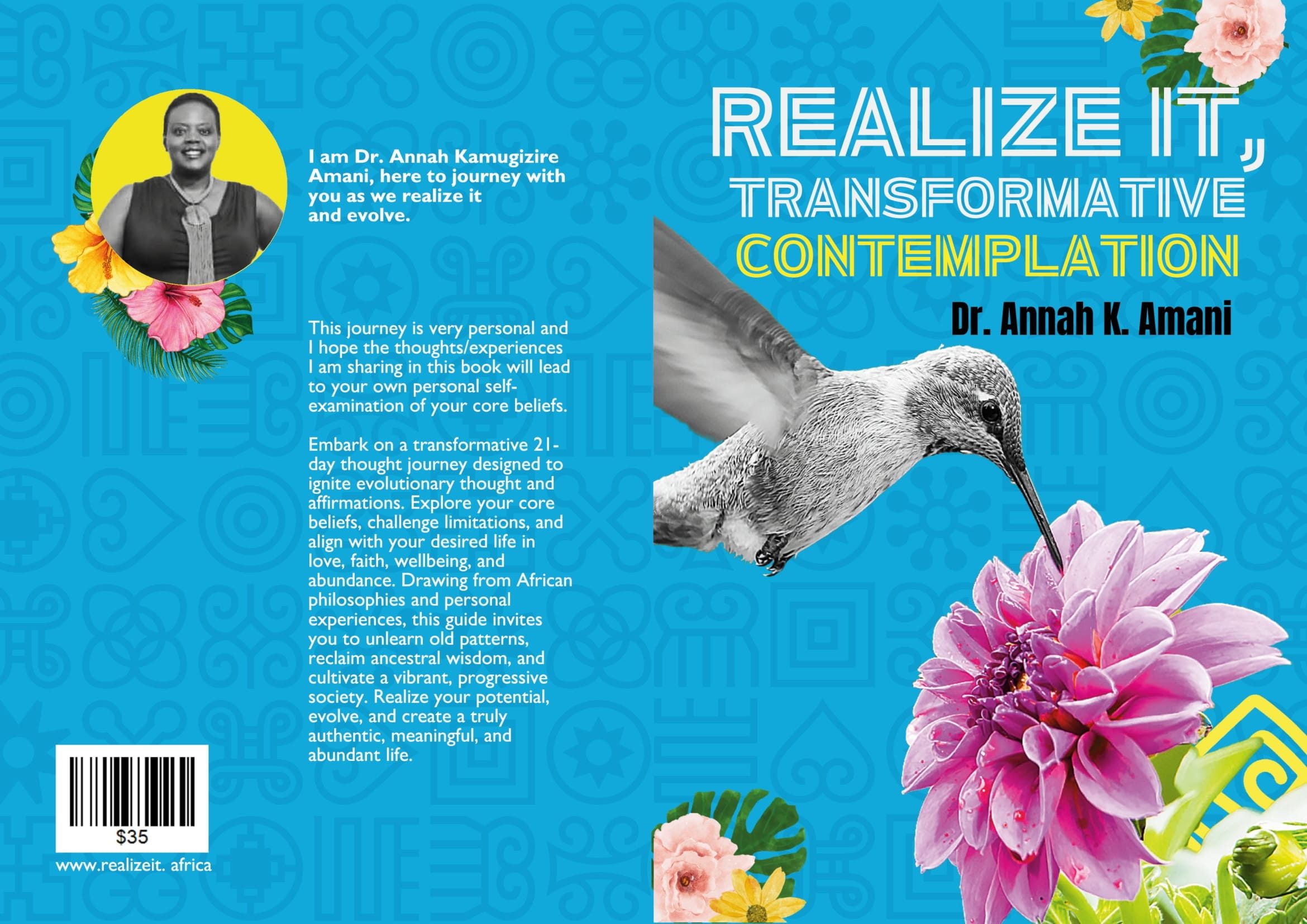

Dr. Annah K. Amani’s Biography

“Whether or not it is clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should.” (Max Ehrmann c.1920) I stared at that quote for quite some time, sitting inside the cramped, airless office of a certain indifferent professor at precisely the moment I was hoping to change the course of the universe, or at least my class schedule. Though the visit to that particular professor’s office was fruitless, that quote was forever etched into a neat little corner of my mind. And from time to time it will come out of that neat little corner to flash onto the big screen of my consciousness.

Do human beings have total freedom to choose their destiny or is everything predestined for us? Though seemingly obvious, in this instance the beginning is a good place to start. I was born in Uganda, East Africa, firstborn to a 15-year-old girl who had been married exactly 11 months to the day of my birth. Her husband was a 30-year-old man and she was his first officially wedded wife. The memories of my life between birth and ten years of age are mere snapshots. My father was a wealthy businessman with political connections that frequently put the family in mortal danger, so we moved. The few snippets I do remember are crowded with people and constant motion. There were always many people in our various households in town, village, Uganda, Kenya; uncles, aunties, cousins, a small army of house help (nannies, maids, cooks, drivers etc.). I remember constantly being brought out to greet this uncle or that auntie. They would briefly comment on what a beautiful child I was and I would go back to whatever I did between greeting aunties and uncles.

While I was busy with my greeting routine, there was a civil war brewing in Uganda. Milton Obote, successor to the now infamous Idi Amin, was engaged in warfare with several resistance movements, including the National Resistance Movement headed by Yoweri Museveni. My father was a supporter of Museveni who would eventually become president. My memories of the war are literally dim ones. I believe due to the constant gun fire and bombing, the sky was always full of smoke. And so I have dim, blurred memories of hiding, gun fire and bomb sounds that would go on through the night, soldiers forcefully entering our house and demanding things. I recall one near death experience after another.

This time of moving around from the dimness of the city to the strangeness of the village ended one startling night. Of this I have a very vivid memory. I was awakened by a tall, very black, strange man and told to help my brothers and sister get dressed. We got on a bus and I woke up to the brightness of a new place. It was bright because we had crossed the border into Kenya and left the oppressive smoke of war behind in Kampala. We spent eight months in hiding in Kenya. During this time, I learned my parents had fled to a place called America and many of the relatives whom we left behind in Uganda, had been killed. My brother and I soon followed on that same journey to America. I think the concept of air travel was far beyond my ten-year-old Ugandan mind. I don’t remember feeling anything extraordinary; it felt like we were sitting in a large building. When we exited that building, the entire world had changed. If I had known about outer space at that point in my life, I would have sworn I had just landed there. Everything was new to me, doors opened magically, moving walkways, escalators; it seemed this entire part of the world was made of glass. After moving through that maze of glass, I soon spotted my parents. My first trip of seemingly millions on the infamous 405 freeway over the hill from Los Angeles to the San Fernando Valley was indescribable. The speed and what seemed like a zillion cars —how was it all possible? I landed in Los Angeles, February 1982. That day marked the beginning of my otherness, a present but separate feeling sunk deep into my spirit. And so I became an observer of the happenings in the glass world. Observing and absorbing all that I experienced. In a few years’ time, assimilation appeared successful and complete. Internally I felt distinct, somehow marked or chosen. I grew up with the sense that my life was marked for profound purpose. By some force which I can only attribute to the divine, my life had been spared time and again; I have survived tribal genocide and civil war. Being a survivor left an indelible imprint on my spirit; a spirit that is remarkably resilient. I have grown up with the conviction that I must make an impact with this life.

The pursuit of profound purpose for my life has taken many forms. All of these efforts centered on the theme of impacting lives, being a catalyst for positive change. This desire to change lives and my mother being in the nursing profession drew me into the health field. Being the eldest child of immigrant parents is a balancing act between family responsibility and personal aspirations. In my undergraduate studies I majored in Health Administration. A degree my family and I thought would be lucrative after four years of study. After immigration, my parents had limited means, and I have worked full time through my entire academic career. While this might appear to be a hardship, ultimately I have gained invaluable skills through this experience. While working full time I received my bachelor’s degree in Health Administration. Then my lofty ideals crashed head on into the sobering entity often referred to as the “real world”. My first job as a new graduate was in the human resources (HR) department of a hospital belonging to a major for profit health care provider corporation. Life at the bottom of the corporate ladder can dull the aspirations of even the most diehard optimist. Needless to say my job as a benefits assistant was as far from my definition of profoundly meaningful as one could get. In the spirit of Zen philosophy, failing to find meaningful vocation, I decided to find meaning in my vocation. Though it was not in line with my original vision, I enjoyed the work and was good at it. I continued to climb the ranks of corporate America and gained experience in various industries, from health care to entertainment. Still in the core of my being I felt myself drifting further away from my purpose.

It was a trip back to Uganda in 2004 that refocused my life purpose and crystallized my vision. Being in my home village after over 20 years in the United States, I felt the overwhelming state of need people live in. I was especially struck by the plight of women and children in poor health with no relief in sight. When I returned to the U.S., I applied for the Master of Public Health program at University of Los Angeles, California. My study emphasis in the program was global Maternal Child Health. Following that two-year program, I took a job with a global non-profit called Unbound. That job took me back to Uganda and I worked with rural communities. It was this work with rural communities that inspired me to pursue my Ph.D in development related studies.

I received my Ph.D from Clemson University in International Family and Community Development Studies in May of 2014. The degree is multi-disciplinary and integrates a wide range of academic disciplines including human rights, social justice, law, education, development studies, humanitarian aid and international research. With its focus on family and community life, the program touches on the most fundamental aspects of people’s everyday lives. Blending the humanities, the social sciences, and various professional disciplines, the program may be unique in its integration of normative analysis (i.e., philosophical, legal, and religious studies), empirical research, and community development. This time of study for my Ph.D. led to a deeper contemplation of my core beliefs and values. Contemplation of my own core beliefs and values inspired the writing of this book to share my life experience and invite the global community to the same contemplative journey. The publication and success of this book would be a progressive move forward in fulfilling my desire for profound life purpose and being a catalyst for positive change in the global community. The seventeenth century English poet John Donne once said; “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.” I am certainly no exception to the “No man is island…” notion put forth by John Donne. To realize my purpose, it will take a multitude of critical moments and the help of many people. This is one of those moments; you are one of those people.